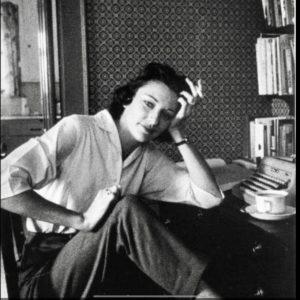

Anne Sexton

- Dec 29, 2024

- 7 min read

Updated: Dec 3, 2025

Anne Sexton was a groundbreaking American poet whose confessional verse exposed the realities of depression, desire, motherhood, and mortality. From To Bedlam and Part Way Back to her Pulitzer Prize–winning Live or Die and the feminist retellings in Transformations, Sexton’s poems, such as “Wanting to Die,” “The Abortion,” and “Cinderella,” broke cultural taboos and gave voice to silenced experiences. Her work remains vital in conversations about identity, mental health, and reproductive rights, continuing to influence poets like Sharon Olds, Ocean Vuong, and Ada Limón.

Anne Sexton was never afraid to write what others refused to say out loud. At a time when conversations about mental illness, sexuality, and the struggles of motherhood were often silenced, she put them on the page with a bluntness that startled and a beauty that disarmed. Her poems, drawn directly from her life, transformed private battles into a public record that spoke to anyone who had ever felt pushed to the margins.

Her first collection, To Bedlam and Part Way Back, introduced a voice that refused to be neat or restrained. By the time she published Live or Die, which won the Pulitzer Prize, Sexton had already shown how poetry could hold both confession and craft. She wrote about suicide, domestic life, desire, and mortality with a candor that made her critics uncomfortable and her readers feel seen.

What made Sexton unforgettable was not only her willingness to break taboos, but the way she did it with lines that could be lyrical and devastating in the same breath. For her, poetry was more than art; it was a lifeline. In turning her most vulnerable moments into verse, Sexton redrew the map of American poetry, proving that honesty itself could be revolutionary.

Early Life and Literary Beginnings

Anne Gray Harvey was born on November 9, 1928, in Newton, Massachusetts, into an upper-middle-class family that looked secure from the outside but left her feeling deeply unsettled. Her relationship with her parents was tense, and the isolation she felt as a child would echo throughout her writing. The sense of alienation, of never quite fitting into the world around her, became a thread that later ran through her poetry with searing honesty.

At nineteen, she married Alfred “Kayo” Sexton II and stepped into the role of suburban wife and mother. On the surface, it was a conventional life. Beneath it, Sexton was already wrestling with depression and the limitations of domestic expectations. The dissonance between how she was expected to live and how she actually felt became central to her creative voice, shaping the themes that defined her work.

Her path to poetry began during crisis. After a suicide attempt in her late twenties, a therapist encouraged her to write as a way to give shape to what she was struggling to contain. What started as a survival tool quickly grew into a consuming vocation. She attended workshops, studied under poets like Robert Lowell, and formed connections with peers such as Sylvia Plath, whose own raw confessional style both influenced and paralleled hers.

Sexton’s first collection, To Bedlam and Part Way Back (1960), announced a new kind of voice in American poetry unafraid to confront mental illness, suburban suffocation, and the complicated realities of motherhood. The book turned the intimate details of her life into art that spoke far beyond her own experience, establishing her not simply as a poet but as a writer who would challenge the limits of what poetry could hold.

Confessional Poetry

Anne Sexton became one of the most uncompromising figures in the confessional poetry movement, her work pushing beyond the boundaries explored by contemporaries like Robert Lowell, Sylvia Plath, and W.D. Snodgrass. Where others approached personal material with caution, Sexton laid bare the realities of her life with a starkness that demanded attention.

Her 1966 collection Live or Die, which received the Pulitzer Prize, remains a defining achievement. In the poem “Wanting to Die,” she confronts suicidal thoughts directly, writing:

“But suicides have a special language.

Like carpenters they want to know which tools.

They never ask why build.”

Lines like these shocked and unsettled readers, not only for their candor but for the precision with which Sexton conveyed the machinery of despair.

She was equally fearless in addressing the conflicts of womanhood and domestic expectation. In “Housewife,” she captured the reduction of female identity to household roles with biting clarity:

“Some women marry houses.

It’s another kind of skin; it has a heart,

a mouth, a liver, and bowel movements.”

By reshaping the language of the ordinary into unsettling metaphor, Sexton illuminated the pressures placed on women in mid-century America.

Her willingness to transform her own pain into poetry that spoke to the collective gave her work its lasting force. Sexton’s poems did not just confess; they confronted, exposing the private struggles of mental illness, gender, and identity in ways that remain urgent and resonant.

Breaking Taboos

Anne Sexton forced poetry into territories most writers of her time avoided, addressing abortion, adultery, sexual desire, and mental illness with a candor that unsettled censors and readers alike. What others dismissed as unfit for art, she transformed into verse that combined unflinching honesty with lyrical control. The result was work that shocked, provoked, and ultimately expanded the very definition of what poetry could hold.

In “The Abortion” from Live or Die (1966), Sexton confronts the subject of terminating a pregnancy without sentimentality or moral judgment. The opening lines cut with blunt force:

“Somebody who should have been bornis gone.”

Rather than offering polemic, Sexton allows sorrow, guilt, and resignation to sit side by side, voicing an experience that had been kept out of public discourse.

Her frankness about sexuality was no less daring. In “You All Know the Story of the Other Woman”, she writes not as judge but as witness, giving the “other woman” depth and complexity: a figure defined by desire, contradiction, and humanity. By doing so, Sexton stripped away the caricature of infidelity, demanding readers confront the gray spaces in relationships and morality.

With Transformations (1971), Sexton took the familiar terrain of Grimm’s fairy tales and bent it into sharp social commentary. Her retelling of “Cinderella” closes with the deceptively flat phrase:

“That story.”

Those two words dismantle the illusion of happily-ever-after, mocking the cultural myths that trap women in roles of submission and sacrifice. Across the collection, she used folklore as a vehicle for examining gender inequality, repression, and the psychic costs of conformity.

By placing taboo subjects at the center of her work, Sexton gave form to experiences that had long been silenced. Her poetry did not simply provoke; it carved out space for voices excluded from the literary conversation. In choosing truth over decorum, she redefined both her era’s poetry and the cultural imagination that received it.

Mental Health and Legacy

Anne Sexton’s career was marked by a relentless tension between her extraordinary creative output and her battles with mental illness. From the start, her poetry was inseparable from her depression, each poem a record of a mind wrestling with despair yet refusing silence. The Pulitzer Prize for Live or Die (1966) affirmed her brilliance, but public acclaim did little to quiet the private turmoil that shadowed her life. Sexton endured repeated psychiatric hospitalizations and multiple suicide attempts before taking her own life on October 4, 1974, at the age of 45.

What remains is not only the tragedy of her death but the force of her art. Sexton’s decision to write openly about subjects that polite society dismissed—suicidal thought, breakdowns, institutionalization—was nothing short of revolutionary. In “Wanting to Die”, she stripped away euphemism to reveal the intimate logic of self-destruction. In “The Starry Night”, she recast Van Gogh’s painting as an emblem of longing and annihilation, entwining beauty with despair. These works turned private anguish into universal testimony, giving readers permission to name feelings they had long carried in silence.

Her legacy reverberates well beyond poetry. By treating vulnerability as material worthy of art, Sexton challenged a culture that equated mental illness with shame. She created a literary space where honesty could coexist with artistry, influencing not only poets such as Sharon Olds and Louise Glück but also broader public conversations about gender, identity, and mental health.

Today, her work continues to be studied in classrooms, preserved in anthologies, and revisited by readers who find in her lines both pain and resilience. Anne Sexton’s legacy is not defined by the circumstances of her death but by the daring of her voice: a body of work that continues to illuminate the darkest interior landscapes and affirm the enduring power of poetry to confront, reveal, and transform.

A Lasting Influence

Anne Sexton’s poetry remains as piercing today as it was in her lifetime, not only for its artistry but also for its prescience. Her willingness to write about abortion, female desire, and the constraints of domestic life resonates powerfully in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2022 decision to overturn Roe v. Wade. Decades before reproductive rights became a renewed national battleground, Sexton had already captured the silenced complexity of abortion in her poem “The Abortion” from Live or Die (1966). Its stark opening—“Somebody who should have been born / is gone.”—refused to reduce the subject to political abstraction.

Instead, Sexton wrote with unflinching honesty about grief, ambivalence, and lived experience, giving readers a language for what had long been hidden.

Critics have noted how Sexton’s work anticipated cultural debates that continue to unfold. By turning her private anguish into art, she broke open the silence surrounding women’s bodies and autonomy, creating a space for literature to challenge prevailing taboos. In today’s climate, her words feel less like relics of the past than warnings and testimonies for the present, underscoring the enduring relevance of confessional poetry in public discourse.

Her influence has stretched across generations. Contemporary poets such as Sharon Olds, Ocean Vuong, and Ada Limón carry forward her legacy of writing that explores the intersection of vulnerability and resistance. Sexton demonstrated that confessional poetry could not only capture the inner life but also engage directly with social and political realities.

Now taught in classrooms and anthologized as a foundational figure of confessional poetry, Sexton is remembered not simply as a poet of despair but as one who redefined how literature could confront society’s deepest discomforts. Her legacy endures in both art and activism, proving that poetry can sharpen cultural memory, amplify marginalized voices, and serve as a form of resistance in times when rights and identities are contested.

Comments