Orhan Pamuk

- Aug 22, 2025

- 9 min read

Updated: Dec 3, 2025

Orhan Pamuk’s long career has unfolded at the intersection of art and political risk, turning him into Turkey’s most celebrated and contested literary figure. His willingness to speak openly about suppressed chapters of the country’s past led to criminal charges, nationalist backlash, and years of security protection, even as his novels reached a global audience and culminated in a Nobel Prize. His continued criticism of censorship and authoritarianism keeps him at the center of Turkey’s cultural and political discourse, where the stakes of telling the truth remain sharply drawn.

Orhan Pamuk’s place in modern literature is anchored in both artistic mastery and the extraordinary risks required to bring his work into the world. His novels probe the psychological and political fault lines of Turkey’s past and present with a precision that few writers have matched, blending archival detail, philosophical inquiry, and narrative experimentation to reshape how global audiences understand Turkish life. His portrayals of Istanbul's class tensions, its shifting identities, and its contested histories changed the international literary map, positioning the city as one of the most complex settings in contemporary fiction.

Publishing work that confronted state taboos, cultural myths, and the country’s unwritten histories required strong, strategic representation capable of navigating international markets while shielding him from pressures at home. The right advocates ensured his books could be released and translated without compromise, giving his voice reach during years when public candor carried real danger.

Pamuk’s recognition with the 2006 Nobel Prize confirmed the scale of his impact, but his influence extends far beyond accolades. His essays, lectures, and public commentary continue to shape global conversations about censorship, national memory, artistic freedom, and the burden on writers working in politically volatile environments. Few contemporary authors have demonstrated a clearer understanding of the risks of telling the truth, nor a greater insistence on doing so anyway.

Early Life and Education

Orhan Pamuk was born in 1952 in Istanbul, a city whose layered history and cultural contrasts would later become central to his work. Raised in the well-to-do neighborhood of Nişantaşı, he grew up in a secular, Western-oriented household, yet remained surrounded by the traditions and complexities of Turkish society. This duality between modernity and heritage shaped his worldview from an early age.

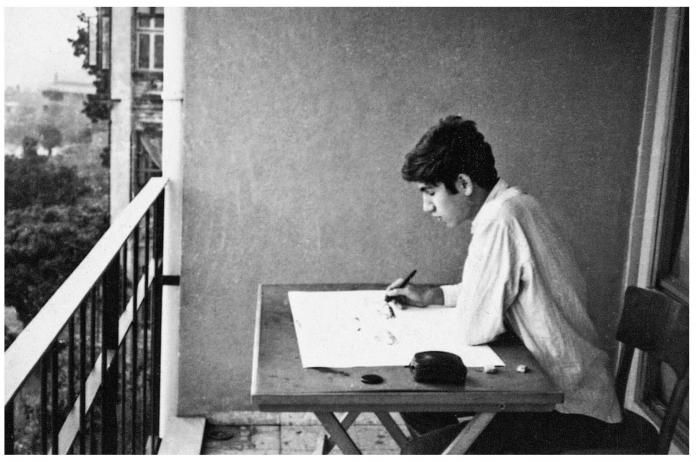

Pamuk’s education initially pointed him toward a different path. He enrolled in architecture at Istanbul Technical University, a choice influenced by family expectations, but soon recognized that design and engineering did not capture his imagination. Turning instead to the written word, he transferred to Istanbul University to study journalism. Even then, it was not the prospect of reporting that drew him in, but the opportunity to immerse himself in literature, history, and philosophy.

By his early twenties, Pamuk had committed himself entirely to becoming a novelist, often isolating himself in his family's apartment to write for long stretches. This period of self-discipline and artistic discovery laid the foundation for his early works. His immersion in Istanbul’s streets, its decaying Ottoman architecture, and its social divides provided both the texture and the themes that would animate his fiction for decades to come.

Literary Breakthrough

Orhan Pamuk’s early rise began with Cevdet Bey and His Sons (1982), a novel that traced the evolution of an Istanbul merchant family across one of the most turbulent periods in Turkish history. Its breadth, precision, and historical acuity earned him the Orhan Kemal Novel Prize and announced a writer capable of carrying national history into the realm of serious literary art.

His reach widened with The White Castle (1985), a seventeenth-century narrative built around a shifting power dynamic between a Venetian slave and an Ottoman scholar. It introduced the philosophical preoccupations that would define his work—identity, doubleness, and the porous line between imitation and selfhood—and its swift translation into multiple languages signaled that Pamuk’s voice would not remain confined to Turkey.

The decade that followed reshaped his creative life. During this period, Pamuk attempted an experiment that few novelists would risk: he drafted two separate books simultaneously, moving between them each day until the psychological demands of the project blurred the boundary between his own interior world and those of his characters. Out of this fraught period came The Black Book (1990), a dense, disorienting meditation on Istanbul as a city of secrets, echoes, and narrative recursion. He wrote the novel in near-total isolation, working for long stretches each day, and later acknowledged that the intensity of its creation left him unsure where imagination ended and reality began.

The momentum pushed forward with The New Life (1994), a novel that broke sales records in Turkey while provoking debate for its cryptic structure and refusal to offer a stable interpretive path. At the same time, Pamuk began the immersive, often dangerous reporting that shaped his later work. While researching Snow, he traveled through regions marked by political volatility and targeted violence against journalists, continuing his fieldwork even as his own name circulated on extremist lists. This period also seeded the conceptual foundation for The Museum of Innocence, a project that grew from a vast personal archive into a fully realized museum in Istanbul, where objects, narrative, and memory converge to create a physical counterpart to his fiction—an undertaking unmatched in contemporary literature.

Major Works and Global Recognition

Orhan Pamuk’s international acclaim reached new heights with My Name Is Red (1998), a dazzling blend of art, philosophy, and mystery set in the Ottoman Empire during the reign of Sultan Murad III. The novel centers on a group of miniaturist painters tasked with creating a manuscript in a style influenced by Western art, only to be disrupted by a murder that forces each character—sometimes even the color red itself—to narrate parts of the story. At once a gripping whodunit and a meditation on individuality, artistic tradition, and the collision of East and West, the book secured Pamuk the International IMPAC Dublin Literary Award in 2003 and solidified his reputation as a novelist of world stature.

In 2002, Pamuk released Snow, widely considered his most explicitly political work. Set in the snowbound city of Kars, the novel follows a poet navigating ideological battles between secularists, Islamists, and nationalists. Through its depiction of religious extremism, personal longing, and the fragile promise of democracy, Snow captured the volatility of modern Turkey while engaging global audiences with its exploration of belief, freedom, and identity in times of political crisis.

Pamuk turned inward with Istanbul: Memories and the City (2003), a hybrid of memoir, history, and cultural reflection. Through photographs, personal recollections, and meditations on the city’s past, he introduced international readers to Istanbul’s hüzün—a Turkish word he used to describe a collective melancholy born of faded imperial grandeur. The book offered both an intimate self-portrait and a lyrical meditation on place, memory, and belonging.

His later works broadened his literary experimentation. The Museum of Innocence (2008) explored obsession and memory through the love story of Kemal and Füsun, accompanied by a real-life museum in Istanbul that Pamuk curated with objects referenced in the novel. A Strangeness in My Mind (2014) portrayed Istanbul’s transformation over decades through the life of a street vendor, weaving personal narratives with the city’s rapid urban change. Most recently, Nights of Plague (2021) returned to historical allegory, situating a fictional Ottoman island in the grip of a deadly epidemic, while probing questions of nationalism, governance, and human behavior under crisis.

Nobel Prize in Literature

In 2006, Orhan Pamuk received the Nobel Prize in Literature, becoming the first Turkish writer to earn the distinction and, at 54, the youngest laureate named in nearly two decades. The announcement reached him while he was under police protection following a surge of threats tied to his public acknowledgment of the Armenian and Kurdish massacres. This atmosphere underscored the personal and political stakes of his work. The Swedish Academy cited his ability to create “new symbols for the clash and interlacing of cultures,” recognizing how he transformed Turkey’s position between East and West into a literary terrain for examining identity, belonging, and the instability of self.

The award expanded his global readership and solidified his standing as a writer whose influence extends far beyond the novel. It also reignited international debate over the 2005 prosecution that had made him a flashpoint for questions of free expression in Turkey. The visibility that came with the Nobel placed Pamuk at the center of a larger conversation about the responsibilities and risks of speaking openly about national history, particularly in a country where such speech had legal and social consequences.

The prize also drew attention to the breadth of his creative practice, which by then included not only novels but expansive archival work, visual projects, and the creation of a museum built from the imagined world of The Museum of Innocence. In elevating him to the highest echelon of literary recognition, the Nobel acknowledged a career defined by formal innovation, political courage, and an insistence on examining the intersections of memory, culture, and conscience.

Controversy and Political Outspokenness

Orhan Pamuk’s status as Turkey’s most visible novelist has placed him at the center of defining national conflicts over history, identity, and speech. Tension erupted in 2005 after he stated publicly that “one million Armenians and thirty thousand Kurds were killed in these lands,” a sentence that pierced one of the most guarded silences in the modern Republic. The reaction was immediate and incendiary. His books were burned at public demonstrations, ultranationalist groups filed a cascade of complaints, and prosecutors charged him under Article 301 for “insulting Turkishness.” The case drew international scrutiny and created a situation in which a Nobel-bound novelist faced the possibility of losing his citizenship simply for acknowledging historical violence.

The atmosphere surrounding the trial revealed the extent of the danger. Threats echoed the rhetoric later used against Hrant Dink, another target of Article 301 who was assassinated two years later. Pamuk was advised to leave Istanbul temporarily for his own safety, and once he returned, he lived with continuous police protection—an extraordinary reality for a literary figure in a country that presented itself as democratic. Even after the charges were withdrawn under international pressure, the hostility did not recede. Investigators uncovered evidence of extremist groups tracking his movements, and nationalist politicians continued to invoke his name as a shorthand accusation during moments of political tension.

Turkey’s political climate hardened in the years that followed, yet Pamuk continued to speak publicly about censorship, state power, and the pressures placed on writers, journalists, and scholars. His criticism of the government’s tightening control over cultural institutions and its prosecution of dissent placed him in direct opposition to dominant political forces. Attempts to reopen investigations into his work—including a 2021 effort to claim that one of his novels insulted national symbols—demonstrated how persistently he remained a target.

Pamuk’s engagement with these issues reflects a commitment to intellectual autonomy even when the personal cost is high. His willingness to address topics many public figures avoid has shaped international understanding of the constraints faced by Turkish artists and thinkers, and reinforced the idea that literature carries responsibilities beyond the written word.

Legacy and Influence

Orhan Pamuk’s body of work holds a singular place in contemporary literature, fusing postmodern experimentation with the layered history and culture of Turkey. His novels operate on multiple levels: they are deeply rooted in Istanbul’s streets, voices, and traditions, yet they resonate far beyond national borders with themes of memory, faith, love, power, and the search for identity. By transforming Istanbul into both a setting and a character, Pamuk has reshaped the way the city is imagined worldwide, making it synonymous with the interplay between East and West.

His impact reaches beyond the page. Pamuk has used his platform as a Nobel laureate to engage with global debates on democracy, censorship, and cultural preservation. His creation of the Museum of Innocence, a physical museum inspired by his 2008 novel of the same name, demonstrates his belief that literature is not confined to text but can expand into lived cultural experiences. As a teacher and lecturer, he has influenced new generations of writers and thinkers, broadening the role of the novelist into that of cultural curator and public intellectual.

With his works translated into more than 60 languages, Pamuk remains both Turkey’s most prominent literary figure and a global voice whose storytelling challenges divisions of geography, religion, and ideology. His legacy lies in proving that literature can carry the weight of history while still daring to imagine new ways of seeing the world.

Comments